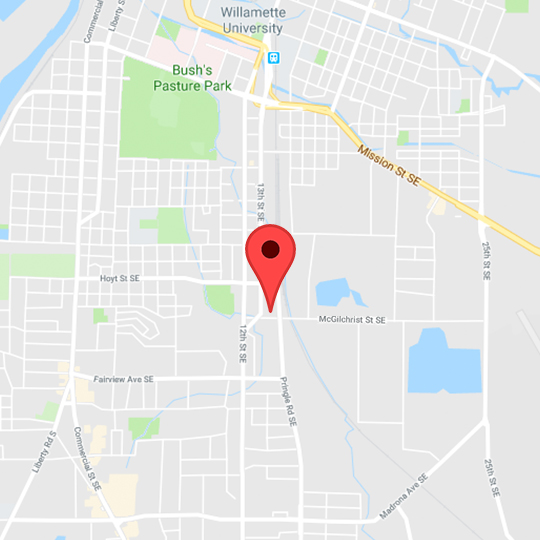

Exhausting, complete overload likely describes the emotional state of many first-time (or even experienced) moms and dads: Sleep deprivation, sore nipples for breast-feeding moms, and visitors showing up at all hours can put a damper on this once-in-a-lifetime experience. So why does baby have to create mayhem with an array of potentially scary behaviors and rashes?

Described here are normal patterns in newborns, which most often generate questions of concern by anxious parents:

“Doctor, he breaths too fast,” or its mirror image, “Doctor, he stops breathing!”

These both represent periodic breathing, then normal pattern for newborns. Babies lack the sophisticated sensors used by older children and adults to very precisely regulate levels of carbon dioxide, the waste gas. As a result, babies first stop breathing, normally, for up to 15 seconds. That’s a quarter of a minute! In fact, we don’t call it apnea (as in doesn’t breathe) until 20 seconds have elapsed.

When the brain finally realizes the baby has too much carbon dioxide, the result of all those seconds without a breath, it overcompensates, but commanding the baby to breathe rapidly for a while. How long? Until the carbon dioxide level is very low. The brain then only has one option: stop the breathing! You get it, the cycle starts all over again.

The baby’s nervous system quickly matures, so typically even by a month of age, the periodic breathing pattern has largely disappeared.

“Doctor, she snorts when she breathes!”

If you listen carefully, you will notice that this snorting always occurs as your baby is breathing in. Even more specifically, when she’s breathing in hard, as she cries, or is falling in to REM sleep, or is feeding.

So what gives? Your son’s nostrils are made of cartilage, not bone. When he breathes in fast, he creates airway turbulence, which has slower pressure: think of the airplane bouncing as it crosses the Colorado Rockies: first turbulent low-pressure air drops the plane, then laminar or smooth, high-pressure air lifts it again.

So the swirling air inside the baby’s nostril creates low-pressure, dropping the nostrils closer together, producing the snorting sound.

The proof that nothing is amiss, is that Samantha just fed well for 20 minutes, something that would be impossible to do if she couldn’t breathe.

“Doctor, Billy-Bob keeps spitting up, when should I be worried?”

Spitting up, referred to by doctors as gastro-esophageal reflux, is universal in babies. In fact, all humans, young and old, reflux multiple times per day, though in the vast majority of cases it is silent, and causes no discomfort.

The spitting by babies is, with rare exceptions, a physiologic event (normal) as opposed to a pathologic event (abnormal, requiring treatment with medications)

Here’s why babies spit so easily: All humans have two muscles, or sphincters in the esophagus: the upper esophageal sphincter prevents us from inhaling too much air into the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes during feedings to allow air which has built up in the stomach to be released “up the chimney” of the esophagus.

To get an idea of why there is so much excess air, it has been said that to match the volume of breast milk or formula consumed by an 7 pound baby, a 160 pound man would have to drink 8 gallons of milk. You would be a bit gassy as well!

So when is spitting abnormal? It can be if it’s consistently associated with crying during each and every feed. This is a bit of a soft sign, however, as the average 2-3 week-old baby cries 2 hours a day, sometimes making it difficult to determine if it’s actually caused by esophageal irritation during feedings. The absolute indication of pathologic reflux is inability of the baby to gain weight adequately.

So be sure to ask your doctor about it if your baby frequently spits up, but be aware at the same time, that most babies will improve, without treatment, over time.

“Doctor, Ramon jerks a lot when he’s sleeping, is that ok?”

Yes! This is another normal variant. Autonomic jerks occur, occasionally, even in adults. In normal full-term newborns, whose nervous systems are only about 60% mature at birth, they are a normal fact of life. And they typically diminish rapidly, even in the first month of life.

“Doctor, Rachel looks like she has bruises on her back, I swear I didn’t hit her or drop her.”

Mongolian Spots, generally confined to the back, are virtually universal in children of color, from Hispanics and Latinos to children of Asian or African ethnic groups. Amazingly, they occur in 5 to 10% of Caucasian children. Only if a child has extensive, persistent Mongolian spots (which I have never seen) over the entire body, trunk, and extremities, not just the back, would we investigate for rare conditions such as inborn errors of metabolism.

These lesions are life-long, and sadly, some parents have been inappropriately accused of child-abuse.

Doctor, Isaiah looks like he has zits on his body. Are those ok?”

Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum is the grandiose medical term for an very common (50% of babies, usually days 2-5 of life) rash consisting of multiple red blotches, usually with yellow bumps, or even tiny pus-filled swellings overlying the red area. No one is sure exactly what causes the rash, though some think it might be due to activation of the immune system. The key, however, is that they are harmless, don’t bother the baby at all (they look like they should be itchy!), and usually fade over several days, with no treatment!

“Doctor, Samantha has blue hands (or feet, or lips)!”

This is another result of the baby’s relatively immature nervous system (25% complete at birth). The nervous system helps control the distribution of blood through the blood vessels, so babies tend to easily shunt blood from the less important organs, like around the lips, or the hands and feet, to more vital organs like the brain, heart, kidneys, and liver. Even as adults, our hands and feet tend to be cooler than the rest of the body in cold weather; this is simply an exaggerated version of the same phenomenon.

“Doctor, Randy’s elbows pop when they move.”

The “bones” of infants under a year are primarily made of cartilage, not bone. As the tendons move over this softer tissue, they will often create a popping sound. A simple rule to alleviate your concern: if the baby doesn’t seem to experience any pain as the joints pop, it is normal. Clearly any pain associated with such popping needs to be evaluated.

“Doctor, Elaine drives us crazy, especially at 2 AM, with her hiccups after she feeds. And I think she has a cold, she keeps sneezing.”

Hiccups and sneezing are yet another example of the lack of control of the newborn’s nervous system. Young infants lack the nervous system control which adults use to generally suppress hiccups and sneezes. Fortunately, both of these normal phenomena dramatically lessen over the first 4 to 6 weeks of life.

“Doctor, Edward’s left eye keeps draining, sometimes it looks like pus.”

Tears are drained by an elaborate drainage system, consisting of tiny “drainpipes” in upper and lower lids, which drain into a reservoir at the inside corner of the eye, at the nose, called the lacrimal sac. This sac in turn, drains accumulating tears down a long duct into the nose. The catch is that there are 3 valves within this drain duct, and in newborns, they invariably don’t work well.

As a result, tears accumulate. In older children and adults, as long as the lids are open, those excess tears keep evaporating. Newborns, however, are sleeping 19-22 hours per day, so guess what? Those tears just sit there. And because the tears, which carry oxygen to the cornea (the only tissue in the body without a direct blood supply), are composed of sugars, protein and fat, they dry into a yellow, sticky glob. This glob is often misinterpreted as pus, which tends to be creamier and greener.

The vast majority of infants (99%) will clear these blocked tear ducts by 13 months of age, and many are already better by 4-6 months. Ask your provider how to massage the tear sacs to help eliminate this. And if you ever think you see green or creamy discharge, or a red swollen area at the inside corner of they eye, call your provider for an urgent appointment, as the blocked tear sacs infrequently become infected.

“Doctor, Allison has a bump between her chest and her tummy, and a ridge down the middle of her tummy.”

The Xyphoid process of and older child or adult is rigid, pointed toward the back. In young infants, it is softer, flexible, and points up. I like to call it the baby’s “diving board,” for if you gently push on it, it will move down like a diving board being jumped on. Usually by a year of age, the xyphoid process is pointed back and you will no longer see it.

Because of the forward-pointing xyphoid process, the Heimlich maneuver to force objects like meat chunks out of the airway should never be used on an infant: The xyphoid could tear the liver, causing massive bleeding.

The soft ridge going down the middle of the tummy is simply the relatively weaker elastic band between the bigger tummy muscles, the recti. When the baby strains as when she’s crying, the bowels push up: because the elastic band is the weakest part, it bulges up a bit. When you press on it, it’s soft, “squishy,” because you’re feeling the bowels under it! It will resolve, like most of these other phenomena, usually by a year of age, and requires no intervention.

This article has been updated.

and then tap "Add to homescreen".

and then tap "Add to homescreen". Salem Pediatric Clinic

Salem Pediatric Clinic